Faces of Law: the Formians

For Pathfinder 1e rules on playing a formian as a PC race, look here

Introduction

by Borssian Engine

It all began with ants

Graybeards say that Arcadia is the celestial home of all insects, that the souls of bees and ladybugs travel there when they die, just as the souls of wild beasts travel to the Beastlands and domesticated animals let their spirits fly the Bytopian way.

Whether that’s true or not, it’s true that many types of eusocial archopods, giant and mundane, dwell in Arcadia’s plains and glades. In places, you can hardly trip over a rock without smashing your face into some sort of hive. A lot of the creatures you find in hives there aren’t even insects—you can find hives of eusocial spiders, monkeys, and fish, acting just as organized as any ant.

But ants seem to have a special place in the plane. There are ants there that have found niches ants on other planes haven’t even thought of—aquatic ants, arboreal ants, ants that produce milk, cheese, and fine sausages.

Then there are the formians.

Formians aren’t so ancient, as planar races go. Their records, which are thorough, date only to the reign of the Rain King FeZan. Before then, they keep records inherited from other races, mainly the now-vanished vaati. These texts mention the formians, but treat them as if they were sub-sentient allies, like their Hounds of Law.

A scholar with enough time and access can see clearly how much more sophisticated the writings of the formians grow in the next few generations. The race seems to have developed astoundingly quickly, possibly in response to the vacuum left by the destruction of vaati civilization in their wars against Chaos. By the time of the reign of the first Scion Queen Mother Kk’kk, their histories were as complex and rigorous as those of the vaati themselves.

Compare this to the degeneration of the vaati descendents. The buseni barely have a culture, while the protectors and the remnant vaati themselves are found only in the most isolated settlements on far-off planes, mostly unable or unwilling to planewalk. It seems clear that the plane judged the vaati and found them lacking.

The formians, by contrast, have thrived and spread to many neighboring planes, from Bytopia to Gehenna, from the Outlands to the Astral, Ethereal, and the Prime. They have taken over many of the former strongholds of the vaati on these planes and rebuilt them, making them even more beautiful than before.

But in the process of straying so far from their origin, have they lost their soul?

This is what this study is determined to find out. I am Borssian Engine. I’m a proud member of the Fraternity of Order and, if it matters to you, a dwarf like our late Factol Hashkar. I live in Sigil, where after the change in command at the City Court I have moved to the Clerks’ Ward and the community of like-minded free scholars. In the process I have gained some… unusual contacts whose opinion I have come to value. With some of them, each experts in their own way, I have endeavored to write a book that will challenge the accepted dogma that the formians are loyal servants of Law. I hope in the process to discover what they are instead and what they mean to the future of the multiverse.

- Ozymandias Plebius is a historian, and a good one. The fact that he uses history to demonstrate his Doomguard beliefs does not change the rigor of his research, and I am much indebted to him.

- Seed is a philosopher of the mind, capable of astounding psychological insights. The fact that he is, or was, a Chaosman should not sway you from listening to what he has to say.

- The Vreeth is a member of a race called the Galchutt. It is assuredly a gibbering psychopath who hopes to bring down all creation, but it is also, undeniably, a genius of god-like intellect and a prisoner of the formians for some centuries now.

- Blib is a member of the Guild of Anatomists. The skills she gained as a priestess of the kuo-toa have only aided her in this craft.

- Jennifer Strong belongs to Harmonium, that fraction under the command of Factol Sarin. She has fought alongside the formians on numerous campaigns, and knows their ways as only a soldier can.

- Glee is a formian worker, and my familiar. I have raised her from an egg.

And with that unjustly brief introduction of my associates, we begin our book.

[A note from Jennifer: The rest of us had to convince him to cull down his descriptions of us – he had our whole bleeding biographies there! The book isn’t about us, and frankly the Vreeth was uncomfortable with Borssian’s detail on its mortal life. Where did he even get all that stuff? And believe me, you aren’t interested in how he house-trained Glee.]

Part I: Art, Harmony, Law, and Punishment

by Borssian Engine

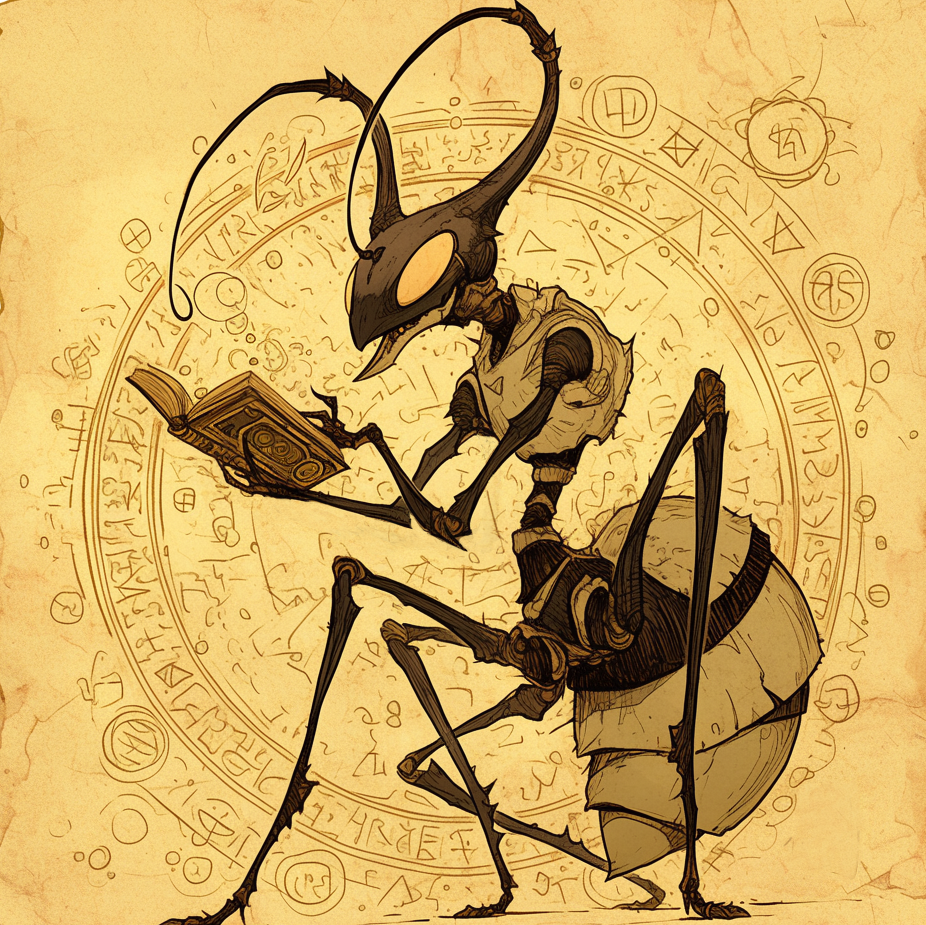

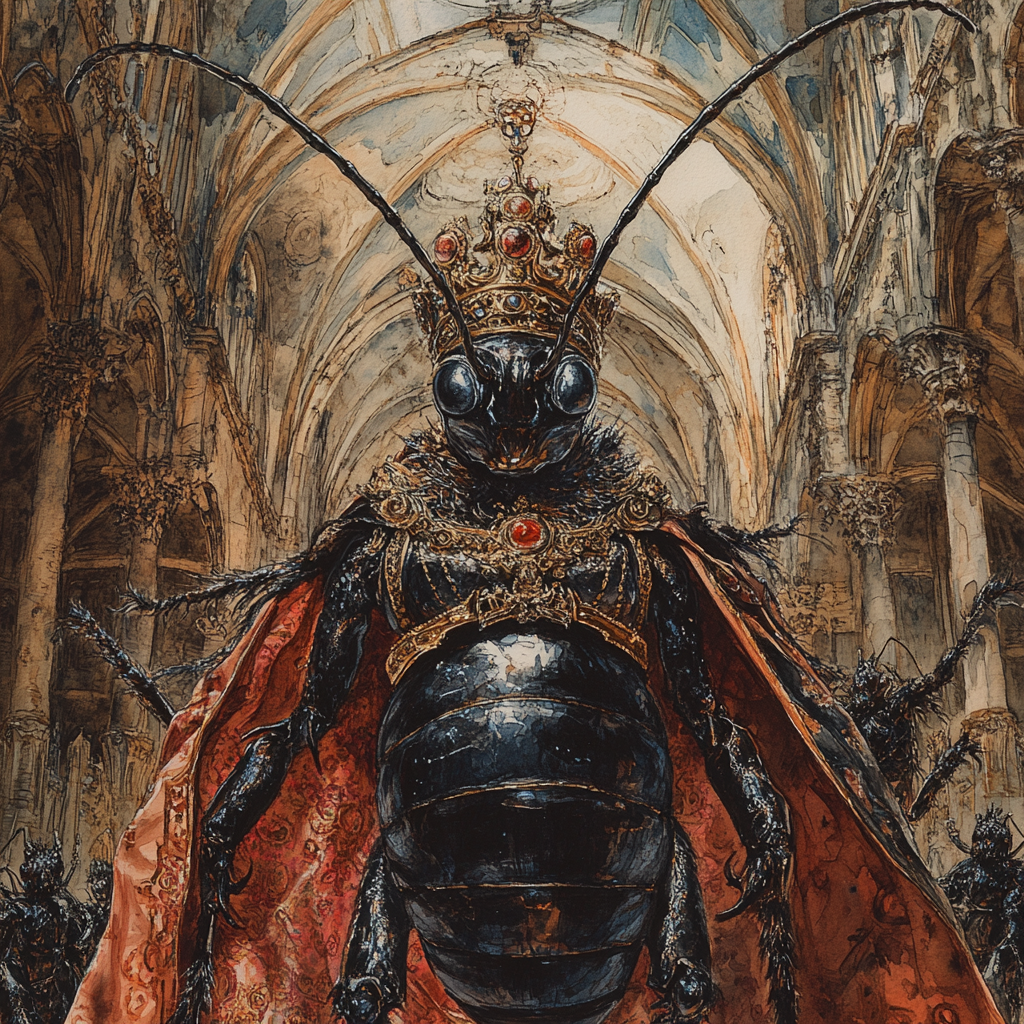

The primary goal of the formians is to transform the entire multiverse into a work of art. This has been, I suspect, always been their goal, though how they’ve approached it over the years has changed.

So let us begin with the formian definition of what art is. Strangely, the formians themselves have no word for art. For them, there is only mxt, life, which encompasses the act of creation and imagination as much as it encompasses breeding and dying. When one formian greets another, that is mxt, and it should be done in the most elegant and conscientious way possible. Formian life-engineers (mxt-tkks) are constantly planning new and better ways to do everything, from better egg-chambers to more pleasing work-songs, to crematoriums that maximize the pathos and dignity of the dead consigned to be disposed there. What we call architecture is the highest form of mxt, for it encompasses all other forms—it provides the setting for the art of living in the most efficient and aesthetically pleasing way possible. Formians take into account acoustics, ergonomics, colour theory, number theory, geometry, and much more.

Chapter One: Art

by Seed

So, ever wonder why so many separate human cultures have pyramids in? Or why the Truffidian civilization seemed to spring up overnight? Me neither. But the reason why turns out to be formians. They’re the ones who invented architecture. All of it. Not wheels and roads and things—they have workers for that.

As a species, formians seem perfectly engineered for creating art. The workers secrete dyes of various colours through specialized glands. These pigments can be used in a limitless variety of media: they can be mixed with cement, with molten glass, with ceramics, with egg tempera, canola oil, water, plaster, adobe, and any other material used by formian builders. Each individual can make only a single colour, but each contributes to make the hive a rainbow of colour.

Formian eggshells, when ground and mixed with water, make a strong mortar that does not readily disintegrate with time. Formian exoskeletons, shed once a century, make a useful grit in concrete and bricks.

As an artist myself, I’ve used formian materials when I can get them and can vouch for their superiority, but they do not restrict themselves to materials they themselves have made. Formians believe the whole multiverse is their pallette and their canvas. Not only do they believe in making use of every material they encounter, they believe it is their moral duty to do so. Not only do they build in every environment imaginable, sculpting the terrain and the structures they create into unified works of art, but they have declared that it is their manifest destiny to do this until every square inch has been recreated by their tools and bodies. As of this writing, they have a long way to go before their goal is achieved. They have cities of warm ice in Ocanthus and Stygia, cities of harmless flame in Mercuria and Phlegethos but they have not yet spread far beyond the planes of Law. Of the Chaos planes, I have only heard of them in the Abyss and Carceri, and there they are seriously outclassed. The last attempt by the formians to colonise Limbo ended in utter disaster as their structures mutated and turned against them—although by Limbo’s standards, that particular work of art was and remains unsurpassed, which might explain why the pseudo-living (hells, call them living) ruins still remain there and even grow with the passing of time.

Now, I know the stereotype of the races of law is staid, uncreative sameness, tradition over innovation. The formians break with this stereotype. At least as far as architecture goes, there is no species more innovative. The Infinite Staircase does not lie. Or, at least, when it does lie the lies become truth.

Formian cities are so well-engineered that they seem to defy gravity. They reach for the heavens: they soar. At the same time, they tunnel deep under the earth, uncovering treasures and secrets. Alone of the tunneling races, formians create subterranean cities that even surface-dwellers can appreciate.

Connecting the sky, the surface, and the underworld like this. Some would say it was not meant to be. Does not the increased communication between the three worlds enhance the potential for chaos? If they succeed in their goal of reshaping all of the multiverse, won’t chance necessarily be as much a part of their final creation as order? Are the formians really, then, personifications of law? Might they not be on our side?

Chapter Two: Harmony

by Jennifer Strong

When all voices contribute to the same chorus, there will be Harmony. When all the planes complement one another, when all voices ring in syncopation, there will be peace.

Still, sometimes I worry. In some planes, there can be no harmony. You can’t make multiversal peace from materials gathered in Pandemonium and the Abyss, yet that is exactly what formians attempt to do on occasion. They believe their taskmasters can pacify the most vile creatures (you’ll have to hear from the Vreeth for more on this), and make them productive members of society. We of the Harmonium are willing to give anyone a chance, but some things you just have to destroy. A wise Prime once said that you can’t build a temple on a foundation of sand. Formian sand castles might be lovely, but they’re not functional. I hope they learn the Truth of this without too much pain.

To formians, Harmony is an aesthetic problem that affects everything from the way they arrange their meals to the way they delegate the tasks of their people to the way they hope to arrange the planes themselves. To formians, Harmony means keeping disparate elements in balance so that each has its opportunity to shine. This is not so different from what we of the Harmonium mean, but the formians lack the overall goal of peace. While it is hard to imagine that a multiverse dominated by formians would have war in it, I suspect sometimes that the formians would stage battles between their own hives if they had no one else to fight. I’ve heard that on the Material Plane, far from the purity of the planes of law, they do just that.

Chapter Three: Law

by Borssian Engine

And so it falls to me to discuss the formian approach to law. Law, for most lesser formians, is not separable from obedience. My familiar Glee will pine if I do not give it regular instructions. For elite workers, myrmidons, and queens, however, it becomes something more. And perhaps the warriors too know something of aesthetics in their approach to combat, even the brutal armadons.

Formians are very concerned with harmony and symmetry, on the principle that each part of something should reflect the greater whole; in this way, they say, every portion of a creation obeys the master plan. For example, the largest formian settlements contain many different “mounds” (actually complex structures resembling human or dwarven cities) all connected to a much larger underground system. Each of these “mounds” resembles the other, with small variations intelligible when the settlement is viewed as a whole.

Formians prefer to have things to relate to one another with simple mathematical ratios, particularly the two-to-one ratio evident in the relative mass of their khuzdid (or hominid, if you must) and insectoid parts. The thought of everything following the mathematical laws of nature appeals to them, as I admit it does to me.

I would even go so far as to suggest that formians personify the principle of the multiverse that tends toward aesthetic organization. The aesthetic principle of the multiverse. To them, this is the highest law that guides all others.

Chapter Four: On Formian Crime and Punishment

by the Vreeth

The parchment you have given me to scribe my thoughts on is dead and dry. It cannot truly convey my experiences any more than you can discover truth in the mouth of a corpse. Yes, I know your spells for speaking with the dead; no mortal magics are unknown to me. Those spells cannot snatch the truth; they are too bound with the rules of magic, and rules are to truth as bureaucracy is to efficiency.

But I will try. I will try not because I value your mortal pursuit of knowledge—though I have found it an invaluable tool in the past—but only because my words (inadequate as their medium may be) may doom my formian captors. They have doomed many others, after all. They are doom itself, as are all things Galchutt.

Try to imagine, if you are capable of such a thing, the page you read writhing with its own life, screaming as your eyes steal bits of its essence, and laughing as it in turn steals essence from you. That is material worthy of a Vreeth, but the formians will not permit chaotic technology in their nest.

The formians are like the corpse, and the pathetic law-magics that animate it. They are mere appearances, subject to the decay and dissolution which are the most real experience a mortal can hope to have. They are without truth or meaning.

The mortals wish me to write about something more specific, however. The mortals wish me to write on the subject of punishment, and the subject of crime. For the reasons I have already mentioned, I will do so. May the doom of all come swiftly.

What, then, is crime to a formian? Formians hate what they view as unaesthetic, which is anything they have not modified to their liking. This includes any and all chaotic acts, many good acts, all of the actions associated with the planes of evil. In their minds it must all be corrected by their taskmasters under the direction of the queen. Damaging other formians is considered criminal, as is damaging other sentient life in a way not made necessary by their greater duty. Damaging the landscape in an overly chaotic manner is considered just as criminal, as is damaging any formian-created architecture or art. Creating art deemed unsatisfactory is considered damage. In nearly every way, formians look at the multiverse as an ideal only the Queen can fully see and only the formians can fully realize, and crime as anything that fails to live up to this ideal.

What is punishment to a formian? Imprisonment is one. They’ve bound me, and my kind cannot be bound. They’ve bound other things, nearly as improbable: dragons, slaadi, emotions, lives. They’ve built towers, empires of imprisoned desire. Like their baatezu cousins, they think in iron and chains. Imprisonment to them is not merely caging a being in physical boundaries, as they have done to me (though my prison is much more than physical); it is imprisoning their mind, their will, their allegiance and their dreams. Not that a Galchutt can dream.

Formian wizards and psions have found many ways to make prisons, subtle coiling formulae that encompass the fabric of the planes themselves. I am staring at my prison. I will find the key to its unraveling. This key will serve me well, I think, in unraveling much more than my own cage.

On the other hand, formians don’t see slavery as any kind of punishment at all. They don’t even see it as slavery; they see it as the appropriate role that certain creatures should serve in order to further their vision of perfection. Formians themselves don’t object to any tasks they are asked to do in pursuit of their racial vision, and they consider it terribly unaesthetic and wrong for any other beings to do so. It is has even happened that formians have calculated that the most appropriate punishment for intractable slaves is to be set free, though this is uncommon.

Formians are reluctant to use torture (other than the torture inherent in imprisonment) or other methods of negative reinforcement. They consider them to be unnecessary, and more importantly unaesthetic. Like their frequent allies, the Harmonium, they would much rather turn others to their cause than waste energy in needless punishment or vengeance. This is a preference the Galchutt understand, though it does not inspire any sympathy.

A far greater punishment than imprisonment from the formian point of view is exile. Their identities as members of a hive are integral to their sense of self. Without their hive, without the comradeship of their fellows, the obediance of their lessers, and the presence of their queen, they pine. They feel like organs divorced from their bodies: like amputated heads that live still, or hands made sentient and kept in a jar. I have witnessed all of those things—formian, head, and arm—even caused them to happen, and yes: they are very much alike. Exiled formians are bruised and wounded creatures in an emotional sense; most commonly they attempt to find another orderly system that will accept them, and they are willing to resort to systems they would ordinarily consider very unaesthetic indeed. “Factions” like the Harmonium and Fraternity of Order they will join very readily; the Harmonium more than anything, for they crave the sense of fraternity the so-called Hardheads promise. Often, however, crimes considered too great for the formians to tolerate are not tolerated by the Harmonium either, and though the Harmonium is renowned for its forgiveness and willingness to consider an entity’s slate clean after proper reeducation and reconditioning, formians are not always able to make themselves feel the remorse for their crimes that the Harmonium insists on, or they are unable to properly communicate this remorse to humanoid minds.

Formians sometimes adjust well to the Sensate faction, for they offer a perspective Sensates often lack and share a common delight in the creation of objects for purely aesthetic purposes. As part of the greater Sensate community they interpret urgings from their superiors as commands, and throw themselves into this new existence fully, doing things tame formians would never dare to do. They see the Sensate hierarchs as their new myrmarchs and queens, the Sensate mission as the new artform that it is their duty to propagate across Creation.

Formians who join the Mercykiller faction become every bit as alien to their kind as Sensate formians. They make an art of punishment and pain, or an art of finding ways for criminals to pay for what they have done. As I have intimated earlier, most formians find this very ugly indeed.

Formians rejected by every potential hive might come to sympathize with the creed of the Bleakers, persuaded that their own lack of purpose is symptomatic of a multiversal lack. They might even join the Heralds of Dust, their exile from their former life convincing them of the all-pervasiveness of death.

A formian would have to indeed be desperate to join groups like the Doomguard or Hands of Havoc, but it has been known to happen. Surprisingly, they follow even these destructive or confusing orders with eagerness and conviction, coming up with surprisingly destructive or confusing ideas on their own. Perhaps they are, after all, not as orderly as their common Arcadian environment has made them seem.

The extermination of a life force is something the formians will resort to far more readily than simple torture, but like many misguided inhabitants of the time-bound planes they do not appreciate the beauty of it. They consider it to be a final resort.

That is the conclusion of my words on this matter. If my words do not destroy my captors, at least they have dissected them, laid them bare as they attempt to lay me bare, imprisoning them within the categories I have chosen. For now, it will have to be enough, but I have eons, all of eternity, to wait. For the Galchutt, patience is easy and the dissolution of all inevitable. Even the prisons immortals make will fall in time.

Part II: On the Form and Function of Formian Castes

by Borssian Engine

Glee would like me to turn this section over to my colleagues, Jennifer Strong and Blib, while I scratch Glee’s belly. You like that, don’t you, Glee? Yes, you do!

Chapter One: On Formian Castes

by Jennifer Strong

An important part of harmony and efficiency in a command structure is making sure that every member of the organization knows their place. The formians exemplify this like no other race I’ve encountered save only, of course, the modrons. All formians are born into their stations and incapable becoming another without major magical intervention. They have no desire to rise any higher, either, so that’s all right.

Worker castes

Workers are the lowest, most basic, and most ubiquitous members of formian society. They are invariably enthusiastic and cheerful when performing the duties they were bred for, making happy rhythmic chirps as they go about their tasks. They are manual laborers, janitors, hunters of vermin, gatherers of grain, nursemaids, messengers, servers, bussers, the assistants of doctors, artists, and smiths. They also assist warriors in battle (alongside formian warrior-clerics), using their powers to heal them when necessary. In formian orchestras they are good at making certain sounds at designated times, but complex solos are beyond them.

Elite workers are far greater in status and intellect to common workers. They are skilled laborers, architects, engineers, smiths, composers, musicians, artists, wizards, magewrights, and mathematicians. After the queen decides what she wants done and the taskmasters figure out who should get it done, the elite workers figure out how to do it.

Warrior castes

Warriors are bred to kill, or to enforce the desires of the Queen with the threat of killing, and when they are not doing one of these two things they do nothing but prepare themselves for this role. They may also train in battle-magic, clerical magic, or psionics in order to supplement their physical prowess. Armadons and winged warriors are other specialized soldier castes, equal in status and essential purpose to other warrior formians. Other specialized warriors include the semi-aquatic mariners, speedy runners, and subterranean sappers. I’ve heard rumors of formians bred to be walking fortresses and living ships, but I’m not sure if this has ever been accomplished or if it’s just a plan for the future. Formian warriors tend to be grim and serious, a sharp contrast to the ebullient workers.

Observers are scouts in military matters and quality control experts in other situations. They watch workers and warriors to ensure that they are able to fulfill their duties satisfactorily and report their findings to the taskmasters. They report the results of each battle for the taskmasters to record into the hive’s archives and for the myrmarchs to use in future planning. They watch the taskmasters to make sure that if they have too much work to perform at once they can inform others to take over for them. They watch members of other races for signs of unrest and dissent. They spy on the lesser queens for the great queen. Those who observe outside the hive may train in tracking specific creatures through the wilderness, or they may specialize in hiding in shadows and moving silently so that they can spy on other races undetected. Others specialize in divination magic, though they must find ways to compensate for their inability to speak the verbal components of spells. Psychic powers are usually a better fit.

Taskmaster caste

If you dismiss the taskmasters as mere slavers, that just means you don’t know anything of formian society and psychology. The formian tongue doesn’t even have a word for slavery; to them to obey the instructions of the Queen, as conveyed through the taskmasters, without question is the highest joy, and they are truly incapable of understanding why taskmasters need to use their abilities to enforce this on other races, and this role is only incidental. To other formians, taskmasters are bureaucrats, essential ones who keep the hive organized and ensure that each formian performs the duty she is most suitable for. They are the lynchpin of formian society; without them the hive would collapse into anarchy, or what would seem like anarchy by formian standards. They create and file the paperwork that records and schedules all the hive’s tasks. They manage the hive’s finances. They keep track of the hive’s food stores, and agricultural schedule. They track the hive’s supplies, what needs to be replaced and what needs to be purchased from other races or hives. They are the historians of the formians. Some are sages or teachers. They are the order of the formian race incarnate. Those who specialise in managing other races, however, may train to enhance their psychic abilities in order to do so all the better, or they might train as wizardly summoners, abjurers, or enchanters.

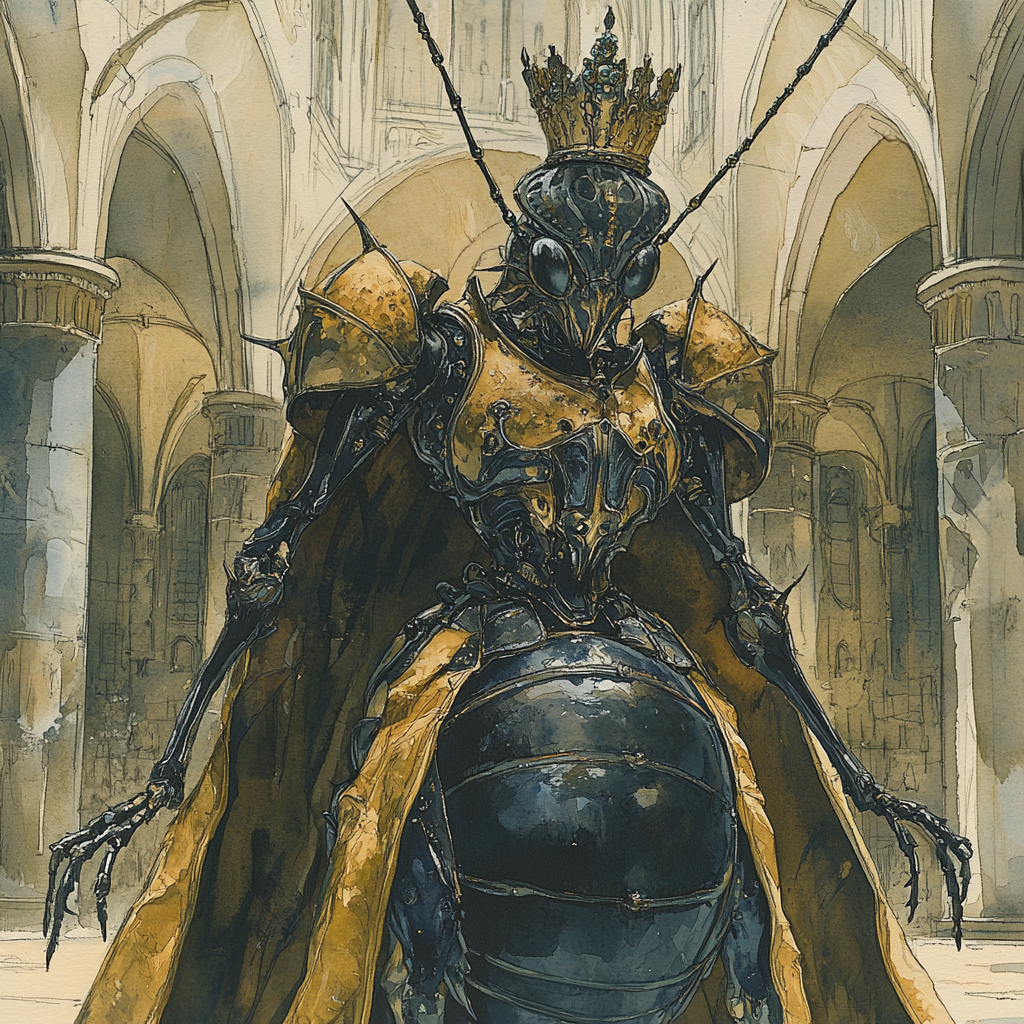

Noble Castes

Myrmarchs are the nobles of the hive. They lead the warriors in battle, debate policy, and advise the Queen. They draft laws for the Queen’s approval. Like all formians, they never question their place or seek to become greater than what they are, but they may and often do scheme among themselves to help their pet interests and projects get a higher priority in the eyes of the Queen. Because all of them are fertile males, they also mate with the Great Queen and compete for her attentions. Due to their great charisma and presence, some myrmachs have become very proficient sorcerers.

Queens are the rulers of the formians. The great queen leads the hive in all things, while her daughters the lesser queens rule the lesser districts or aspects of the hive to which their mother assigns them until they leave to found hives of their own. Most formian hives have no more than ten lesser queens, though the largest can have a hundred or more, all overseeing substantial regions of the formian metropolis. Although they may ask and take advice from others, the queens are the ultimate decision-makers among the formians, and none may disobey them once their decisions have been made. Lesser queens have been known to scheme to gain more power for themselves. They are the only formian caste that does so, probably because power is something they are bred to take. Some queens are sorcerers or priestesses as well as rulers.

The only entities greater than a queen are, perhaps, the gods themselves. Formian queens often revere powers of order, fertility, and industrialness, and they pass the duties of worship on to their underlings. Still, the formians know who really rules their hive, and (clerics excepted) if they worship the gods it is only the way they show respect for their great queen.

There is a single greatest queen, the Scion Queen Mother, who lives in the plane of Mechanus in an anthill called the Centre. She’s been reported to have godlike power by those who’ve seen her in person; apparently she’s a true planar lord like the tome archons of Mount Celestia or Primus himself. She even grants spells to the formians of Mechanus, though she may have a god’s aid in this. Queen Clarity in Arcadia is older than her, however, and expresses no allegiance to the Mechanical Mother. The split between the Mechanical and Arcadian formians is ancient, and hopefully it’ll be dealt with more in the history section.

Chapter Two: On Formian Form and Function

by Blib

Many are the forms of the Underdark and the deep sea. Varied and profound is life in the depths, more than even those in the wide planes would ever expect. The shapes of the formians, by contrast, are extremely limited. But then, that is their nature as creatures of law.

From an anatomical perspective formians have very little in common with ants, and I cannot support theories linking the two species. In many ways formians are utterly unlike any sort of arthropods. In fact, most of all they resemble the baatezu of the Nine Hells. In particular they can be compared to the advespa, kocrachon, and gelugon castes, with a similar combination of arthropod and cordate features. Unfortunately, I do not have enough evidence to speculate on a possible common ancestor of formians and baatezu. More likely, the baatezu designed their pseudo-arthropod castes using the formians as a model. This would imply that formians are much more ancient than they are given credit for even in their own histories; I believe that there must have been a proto-formian species without the intelligence of the current breed, and these; not ants, are their true ancestors. I have no evidence for what might have happened to them after true formians appeared, and I cannot rule out genocide. Many species, including humans and dwarves, have similarly proto-sentient ancestors apparent in the fossil record, unlike the kuo-toa whose ancestors apparently had an even larger cranial capacity than my own somewhat diminished kind.

They are hexapods, like insects and kocrachons and unlike standard-model advespas or gelugons. Their bodies have four basic parts: a head, a kuo-toid upper torso, and an insectoid thorax and abomen. Formian exoskeletons—which are usually brownish-red, though some subspecies possess other hues—have several parts: the tergum, covering their back, the sternum covering their underside, and two pleura connecting the tergum with the sternum. Their upper torsos have a seperate tergum and sternum, connected to the exoskeleton covering their thorax and abdomen by two additional pleura. Their heads are also covered in chitin. Many formians elect to reinforce this with helmets forged from steel or other metals. Contrary to the reports of some clumsy scholars, formians do not have carapaces covering their exoskeletons, as many crustaceans do. Neither, to set the record straight, do kocrachons or any other baatezu caste. In fact, the exoskeletons of giant ants are thicker and tougher than those of formians or kocrachons, though not tougher than that of an advespa’s and certainly not tougher than a gelugon’s.

Adult formian exoskeletons are molted once every century to enable them to grow (and here they are unlike baatezu, who never molt their exoskeletons except in the process of being transformed into another caste). After reabsorbing any useful minerals into their body (a process that significantly weakens the carapace), the new cuticle is laid down underneath the old one; the formian swells up causing the old cuticle to split; and finally the new cuticle is hardened. The whole process takes about a month. Formians molt in four to six “shifts” (depending on the hive) so that those who are weakened by this process can be protected by the others. The old exoskeletons are reused as building materials, a use for which they are eminently suitable despite the mineral drain.

Formian thoraxes, like those of advespa baatezu, are composed of two segments, each bearing a pair of walking legs made up of a coxa, trochanter, femur, tarsus, and pre-tarsus. They lack the third pair characteristic of insects; their only other limbs are attatched to their torsos in much the same way as a kuo-toa’s arms are; these arms are triramous—that is, they end in three jointed branches, effectively two “fingers” and an opposable “thumb.” They have the same basic parts as their walking legs, but are articulated for grasping things in front of them.

Formian abdomens are made up of eleven distinct segments. First is the petiole, then the propodeum, the waist (usually with only a single post-petiolar node), and the gaster, the abdomen proper, which contains the remaining segments. The eighth and ninth segments (also the tenth in myrmarchs) bear the genital appendages; these are vestigial in every caste except the myrmarchs and queens. All formians (like advespa and osyluth baatezu) also have stingers, though these are vestigal in workers (including elite workers), winged warriors, and queens.

Formian heads, like their torsos, though shaped by chitin are almost kuo-toid (humans, themselves kuo-toid, might instead call them humanoid), complete with distinctly visible noses and lower jaws (which replace the maxillae behind an ant’s mandibles), their exoskeletons mimicking the general shape of a kuo-toid skull, perhaps more mammalian than piscine. They also have a single pair of mandibles, which are heavy and have grinding and biting surfaces; mostly, these are used in combat, while their more kuo-toid jaws are used for eating. Like crustaceans (and the visage of the Sea Mother herself), they have compound eyes, though they lack the jointed stalks of that sanctified kind, instead closely resembling water fleas or terrestrial insects. They also possess three ocelli like those of ants capable of detecting differences of light but not shapes. Like insects, advespas, kocrachons, and gelugons, they have a single pair of antennae.

Apart from their eyes and “nose,” sense organs such as chemoreceptors and tactile hairs occur all over the formian body, but are most concentrated on their appendages: the arms, legs, and antennae.

Only a single formian caste, with the practical name of winged warriors, is winged. Their wings are very much like kocrachon or advespa wings, transluscent and seperated by veins; like them, they have a pair of wings growing from both their first and second thoracic segments. As with advespas, both pairs are hooked together so that they move as a single structure. Their front pair is larger than their hind wings, and they have structures at their base called sclerites, which allow their wings to be folded across their body. The winged warrior’s entire body is adapted for flying, like the advespa and unlike the kocrachon (which generally saves flight as a last resort).

Organs

The formian brain looks almost identical to a kuo-toid one, complete with a large and well-developed forebrain. Instead of a ventral nerve cord connecting a system of fused ganglia characteristic of insects they have a very piscian spinal cord, although a series of spiked dorsal ridges replaces the typical piscian spine. Instead of the spiracles and tracheae of terrestrial arthropods or the epidodites or (except in the mariner caste) gills crustaceans posess, they have true lungs. Formian lungs are almost identical to baatezu lungs, but without the scaly surface of fiendish organs.

Their eyes contain about 4000 facets packed together, larger in the front in order to allow them to look directly ahead more easily. Each facet is formed by the cornea of a visual element called an ommatidium, which contains the cone, iris, and retinal cells. The formian hivemind also allows them to share the perceptions of all others of their kind in the area, making them extremely hard to surprise.

A formian lacks a true stomach. Instead, their esophagus (which begins within their head) leads to a crop, midgut, and finally a hindgut in their gasters terminating in their stinger. Organs called Malpighian tubules (after similar ones found in insects) open into the hindgut; where useful salts and water are extracted before the waste products are excreted. This is all very similar to the kocrachon and advespa; gelugon tails contain many of the organs found in insectoid abdomens.

Most other formian organs are located in the thorax and abdomen. Their hearts are four-chambered like a baatezu’s, though again they lack the typically fiendish scaled surface. A formian has two hearts, a small one in the thorax and a larger one in their gasters.

Variations

The workers, not surprisingly, have the simplest anatomy of all formians. Their forebrains are relatively small and smooth like those of advespas or barbazu. They lack the specialized wings of the fliers. Some do, however, have specialized limbs depending on the tasks they were bred for. Forelimbs resembling picks and shovels can be observed in some workers (as well as warrior sappers). In their abomens, workers have glands that produce a variety of coloured pigments used in various projects from weaving to painting to the making bricks and mortar.

Elite workers are similar anatomically to common workers, but of a size nearly equal to the warriors and a cranial capacity equal to taskmasters and observers. Their “hands” are capable of significantly finer manipulation than common workers’ are. They are otherwise anatomically identical to common workers.

Warriors are more than twice the size of common workers. Their stingers are usable and fed by a poison sac that is even more potent in higher castes.

Armadons have a radically different morphology than all other formians but sappers. They lack a kuo-toid upper torso, instead having three thoracic segments. Their middle thoracic segment bears a par of insectoid limbs, twice as large as their walking limbs. These limbs are biamous, with two jointed branches in the form of crustacean-like claws. They have no opposable thumbs, and rely on workers to perform any tasks that require them. Their exoskeletons are extremely thick and tough, making them nearly as well-armored as gelugons. An armadon’s internal organs, on the other hand, are mostly the same as all formians—lungs, spinal cord, and all. The only other major difference is the acid gland in their abdomen, which replaces the pigment glands workers possess.

Mariners are much like warriors, but they have a variety of aquatic adaptations including the gills, telsons (tails), uropods (tail fans), and swimmerets familiar to those of us who have studied lobsters. They are amphibious, and can function just as well on land.

Runners are more or less identical to other warriors, but they have longer legs and lighter bodies (similar to that of the winged warrior) built for speed. They are about half again as fast as most formians, as swift as winged warriors are in flight. However, they are correspondingly less effective in their claw and bite attacks.

Sappers are built like armadons, their pinchers replaced with digging claws. I have never observed one up close, but it is said they can burrow through the earth as fast as an ordinary formian warrior can walk on land.

Winged warriors are slightly smaller than normal warriors, their bodies more aerodynamic and sleek, their abdomens long, narrow, and curved. Their wings are approximately the same length as their body, though as noted earlier they can be folded away when not in use. Replacing the poison stinger of most formians are a series of abdominal spikes which can be fired at opponents from a distance. Although they have mouths, like observers and taskmasters they can commicate only telepathically through the formian hivemind. They have no telepathic abilities of their own unless they learn them through the study of psionics. Exiled winged warriors are thus left mute until they find a way to compensate.

The most distinctive characteristic shared by observers and taskmasters is, of course, their lack of mouth and mandibles. From birth to death, neither caste eats or drinks, nor do they make audible sounds. The formian “hivemind” and taskmaster/observer communication and control seems to all be psionic in nature, as evidenced by their enlarged pineal glands. Without the aid of a psionicist, however, I cannot confirm this. Observers and taskmasters are both about the same size as elite workers, similar in height to a kuo-toa and of a mass similar to a squid or terrestrial pony. They are slightly smaller and more slender than members of the warrior caste, but the difference is not great.

Observers have greatly enlarged head, with a correspondingly greater cranial capacity exceeded in their species only by the queens. They also have two extra pairs of eyes on the backs of their heads, giving them 360 degree vision, and greatly enlarged and more senitive antennae. Its arms end in “hands” nearly as delicate and sensitive as those of elite workers.

Myrmarchs are large, the size of sea lions or terrestrial horses. Physically they are very close to warriors, with an even larger and more potent poison sac. As noted earlier, myrmarchs are all male. They take turns mating with the hive’s Great Queen. When lesser queens leave to found a new hive, harems of younger myrmarchs who have not yet mated go with them.

Queens are enormous, fully twice the size of myrmarchs. The great queens rule their hives and all formians within five hundred miles with their telepathic power. Lesser, virgin queens assist their mothers in this. Unlike the case with ants, formian queens do not lose any brain power when they become egg-producers. If anything, the opposite is the case, as great queens are known to grow more crafty with time.

Gender

Except for the myrmidons and queens, formians are all completely sterile females (like baatezu females, but also like lower-caste ants). They lack ovaries or any other reproductive organs. Queens are all fertile females, while myrmidons are all fertile males. Lesser queens are not permitted to procreate until they have started their own hives, but affairs with myrmarchs they find attractive have been known. If discovered, this is considered adultery and is punished by the exile of the queen and the castration of the myrmarch, who is nevertheless retained for his usefulness in other capacities.

The lesser, sterile castes can simulate mating if they desire it. The frequency with which this is performed varies with the individual. A lesser queen could mate with a sterile female, but this is highly frowned upon in formian society. There is no direct punishment other than social estrangement, but such a queen is highly unlikely to be allowed to ever found a hive of her own. The sterile female is left alone, as she was likely only obeying orders.

Unlike true ants, fertile formians do not have wings and do not mate in the air. They mate within their hives, in private chambers where none but the queen, the myrmarchs, and a few workers are allowed. The process is messy, unlike the more sterile method employed by kuo-toas and other piscians.

Birth and Maturation

Formian larvae hatch from eggs laid by the Great Queen and nurtured by workers. Sometimes infertile eggs will be produced by the Queen as a gourmet meal, either for herself or for guests. Their eggs have hard, leathery, slightly scaly shells, seeming almost reptilian. My best guess is that these shells were artificially introduced to the species, though without more knowledge of the proto-formian race I can’t be sure. The Queen lays hundreds of eggs a day.The larvae are white in color and wormlike, with faces revoltingly reminiscent of human infants. After a year they transform into a pupal state. What they become after that is usually dependent on what alchemical, magical, and psionic processes are performed on them by the adult formians; female larvae can theoretically become any caste except myrmarchs, while the rare male larvae can only transform into myrmarchs. Larvae that are left alone usually become common workers. Turning a female larva into a elite worker, standard warrior, or queen is simply a matter of feeding it correspondingly more; formian workers are extremely precise in the amounts each larvae is fed. The process of creating other castes, such as armadons or taskmasters, is more complex carefully devised by the formian life-engineers.

Once it emerges from its pupa it is in the caste it will remain in for the rest of its life. It molts twice a year for six years until it reaches its adult size. From then on, it molts only once a century.

Nourishment

Formians are omnivorous, but primarily vegetarian; they grow crops and prepare generally simple meals calculated to provide maximum nourishment, though on special occasions formian chefs will create complex works rivaling the accomplishments of their architects. The warrior castes, on the other hand, are given purely carnivorous diets, the meat derived primarily from giant vermin kept in pens, although the formians do not believe in wasting the flesh of fallen enemies.

It has been determined, however, that formians do not actually need any food at all. Certainly the mouthless taskmasters never eat, and all members of the race seem capable of subsisting on the pure substance of Law and the satisfaction they gain from fulfilling their duty. Why, then, the elaborate irrigation systems and windbreaks? Why the complex food processing centers and the devotion of thousands of workers and hundreds of chefs to a task completely unnecessary to their existence? Why not devote all that superfluous energy toward fulfilling their mission?

When asked, formians have replied that the construction of an ideal civilization in all its parts is their mission. What they make and do is not only for them, but for all the peoples of the multiverse who must one day be made to see the perfection of the formian ideal.

Sleep and Dreams

Of all formian castes, only the queens normally sleep. The others remain awake to perform their duties around the clock. The queen spends about one third of her time dreaming, transmitting whatever psychological benefit there is to gain from this to her underlings via the hivemind. Formians away from their queens for extended periods of time manifest the symptoms of sleep deprivation. After about twenty days, however, they adjust. Something seems lost from them forever, however, some spark of creativity that they formally had and now no longer have access to. Exiled formians have tried enchantments or psychic surgery in an attempt to gain access to the dreaming world, but thus far these avenues of exploration have not born fruit. Only return to a formian nest will grant them what they crave.

Aging and Death

Unlike many planar creatures of the type some Anatomists have begun calling “Outsiders” or (more accurately) Planeborne, formians, at least those of the lower castes and those who have been separated for their hives, do seem to age over time. While the mausoleums and catacombs beneath formian hives are kept private, I have reliable reports that workers, after a century or so of life, are seemingly “used up” and become nothing but desiccated husks. Perhaps only the collective, the Hive, is truly ageless, though I also understand that some of the same formian artisans responsible for building key parts of the most ancient formian cities are still alive today—at least, so formian propaganda would have us believe. It’s possible that some creative essence that artisans tap into keeps them alive long after the lesser workers perish, or even that the lifespans of the workers are somehow “deferred” to more valuable citizens through the hivemind. The queens are almost certainly immortal—the one known as Clarity seems to have been around since almost the beginning of the formian race.

Like all known forms of life, including the perishable gods beneath Blibdoolpoolp, formians may die from accident or injury. It’s conceivable that the reported “husks” were somehow the victims of magical attack, or some vampire-like draining seen by the queen as being for the good of the hive as a whole. Perhaps it empowered some spell or ward in an emergency? This is not my field of expertise; the priestesses of Blibdoolpoolp seldom resort to such measures, at least not with those of our own race.

Part III: Time and the Planes

by Borssian Engine

It’s time for Glee to be taken on his walk, so this last portion—which describes how formians fit into the grand schema of History and the Multiverse (the temporal and planar axes, respectively)—will be in the capable hands or other appropriate limbs of Ozymandias Plebias, Jennifer Strong, and the Vreeth.

Chapter One: History

by Ozymandias Plebias

It was in the reign of the first Scion Queen Mother, Kk’kk, that the Egg of the Unborn was shattered. The Egg, claims the volume (forbidden to non-formians—I only have a copy of a copy of a copy, purchased from a rastapede book dealer in the Night Market of the Hive), contained within it all formian souls. Supposedly Kk’kk’s daughter Kk’kl desired that the formians expand beyond Arcadia, and Kk’kk forbade it, reminding her daughter of the fate of the vaati. In a fit of pique, Kk’kl destroyed the Egg, dooming all of formian-kind to soulessness.

Without souls, formians could not create. They had no imaginations, no passions. The entire species began to wilt and die.

It was the formian queen known today as Clarity who provided what was at least a temporary salvation for her people. She found the secret of opening the race to the energies inherent in Arcadia itself, transforming her people from mortals to something else, a fundamental manifestation of the plane. The plane of Arcadia would be their collective spirit, their essence, their drive and inspiration.

And then they began to thrive, and spread as Arcadia wished them to, to spread their particular affliction throughout the multiverse.

This, I must hasten to remind my readers, is merely a myth, and I have no proof to its accuracy or even that, as I believe, it is a genuine myth of the formians. Memory is an ephemeral thing, as the condition of the materials available to me show.

Kk’kl continued to lead her people abroad. Eventually she became the being known in Mechanus as the Scion Queen Mother. Again, I cannot prove this.

I am, however, on firmer ground with my next date. The formians first encountered the group of mortals known as the Harmonium some 300 years ago, when that faction first reached the Plane of Arcadia after its disastrous attempt at conquering the Abyss. They got along well from the beginning; formians believe the Harmonium was itself inspired by a society of mundane red ants sometime near its founding. They found common ground in their desire for universal harmony, and the Harmonium valued formian allies enough that they were willing to take some small amount of formian advice on the form their harmony should take.

The first crisis in formian-Hardhead relationships was not in Arcadia, but in Mechanus. After making a request to begin diplomatic relations at a formian embassy—something they believed would only be a formality—they were not only turned down, but they were not allowed to leave. They weren’t put to work in the mines of a salt cog, not yet. They were simply locked in the embassy, provided with their food and water needs, and made to remain there until more of their kind came to investigate the disturbance. They were, to put it bluntly, bait.

More of the Harmonium did come, searching for their missing comrades. The formians let them in too, but did not let them out.

The next time the Harmonium came, it was as an army. In the end, that particular hive-city was decimated and burnt to the ground, all of its inhabitants slaughtered. Hardheads haven’t been harassed by formians in Mechanus since (although there are still occasional flare-ups on the Prime and elsewhere), but the Harmonium hasn’t been quite as comfortable around the centaur-ants since.

Chapter Two: Relations with Other Races

by Jennifer Strong

Formians are happy—more than happy—to let other races become part of their hives. They would prefer not to have to force the matter; in their minds, all should fulfill their intended roles of their own free will. And, in many cases, they don’t have to force anything: formians have much to offer a culture with little wealth and resources. They can teach their allies how to better themselves, providing them with food, clean water, and shelter, even companionship and a sense of belonging while doing something useful and beautiful to see. Many are those who find this an attractive proposition.

Other insectoid races find it especially easy to adapt to life as part of a formian hive. The beelike abeils and psionic dromites thrive there, making valuable contributions formians couldn’t make without their help. Formians are just as eager to take in subsentient vermin: giant bees for their honey and royal jelly, wasps for protection, giant ants as helpers, giant beetles as beasts of burden and for meat. Arachnids like spiders are valued for their silk and their combat ability.

Formians will also readily breed domesticated mammalian species such as cows, goats, and sheep, and domesticated avians such as chickens, ducks, and geese. They even domesticate wild beasts such as bulettes and wolves with varying levels of success—though they put human efforts in this regard to shame, and are truly a model for the Harmonium to live by.

Humanoid races have more trouble adjusting. Dwarves, goblins, kobolds, grimlocks, and gnomes are best suited to life in formian tunnels, though humans and halflings can often get used to it. Elves, excepting drow, can rarely handle it, quickly developing claustrophobia. The formians are just as glad to let allied races live above ground, though, as long as they contribute to the greater good and let the formians design their homes.

In the Inner Planes, formians are disliked by genies of all sorts, who consider them to be pests. Most exterminate them, although dao prefer to enslave them and put them to work. On the Elemental Plane of Earth formians are particular rivals of the insectoid horde creatures who have taken up much of the plane. Elementals, on the other hand, ignore the formians. Formians have managed to enslave some lesser elemental creatures such as the pechs, geonids, and grues. Their only real allies on these planes are the occasional dwarf or gnome colony and the creatures known as elementals of law: the krysts of earth, helions of fire, anemos of air, and hydraxes of water and ice.

Particularly chaotic and freedom-loving races such as bariaurs, githzerai, githyanki, and eladrins revile formians, and do their best to contain their spread from the Planes of Law, readily killing them if they need to and often even when they don’t. Guardinals try harder to find peaceful means of dealing with them, but will also kill them if that is the only way to stop them from warring on good-aligned creatures. Rilmani leave formians alone unless they grow stronger than the chaotic races on a given world.

Formians do not get along well with fiends, even baatezu, finding them utterly repugnant and unappealing. Formians slaughter fiends when they can, and when they can’t—for example, in their Baatorian colonies—formians pick unpopulated areas where they can simply ignore the baatezu. Still, corruption of the formians by fiends has been known to happen. The Viscount of Minauros and the Archduke of Maladomini in particular is said to have great fondnesses for formian servants, and several rakshasa rajas have been known to make use of formian architects—though even to my inexpert eye, it doesn’t look like anything close to their best work.

The centaur-ants get along better with lawful celestials, particularly in Arcadia where they coexist as mutual allies. They are also allies with other Arcadian races, such as the shape-shifting buseni, the bee-like thriae and the crystalline qu’iiir. In Mount Celestia relations are tenser, with formians being treated as potentially dangerous vermin who nonetheless have their uses when properly approached.

Formians—particularly the formians of Mechanus—are in a tense state of anxiety with regards to the modrons. While they respect the modrons and would dearly like to have modron assistance in their hive-cities, there are many aspects of their architecture and society that they think they could improve. Still the queens, led by the Scion Queen Mother, have held back from declaring war on them. The modrons, for their part, mostly ignore the formians, arresting individuals when something they do breaks one of their many laws. This state, I think, cannot last forever.

Although Seed doesn’t know it, the formians have indeed spread to Limbo. After the formian queen Hvix’mnac’s accidental journey to the plane, she felt confident enough to lead one of her hardier lesser queens to start a colony there. This Limbo colony, unlike all other previous ones, has managed to last with the help of a group of natives—a colony of slaad-like creatures called naraphim—who they have enslaved. The formians and their naraphim servants fight off attacks by slaadi, githzerai, and chaos beasts, and seek to expand.

Chapter Three: On the Cross-Planar Summoning of Formians

by the Vreeth

Calling them: Calling formians to your service can be done with most standard summoning magics, though I find spells that contact the planes of law to be odious. Formian hives anticipate summoners, and the taskmasters assign members of various castes to this duty in anticipation of the spell crystals that appear to take their kind to other planes. They don’t do so with the idea of tempting their summoners into greater acts of law; they aren’t that much like baatezu. It is simply more efficient that way.

Controlling them: Formians respond readily to commands and usually do not hold grudges unless they are asked to perform tasks they find particularly unpleasant. This makes them ideal summoning stock for lawful spellcasters, and a more sensible alternative to fiends.

Rebuking them: Any magics effective against Law and its creatures work superbly in banishing, punishing, tormenting, and destroying those of formian ilk. Though their aspect of Law is different and, I would wager, less pure than, for example, the modrons, it is certainly Law which empowers and sustains them, and any activity baneful to Law is baneful to them.

I will, for the moment, refrain from commenting on the dark joys that inflicting a chaos hammer (or something perhaps more slow and subtle) on a formian worker can bring. You do not deserve to read of such raptures.

Canonical Sources:

Dragon Magazine #354 36,41; Fiend Folio [3e] p76-79 (formian armadon, observer, winged warrior); Manual of the Planes [3e] 127-128, 130; Planes of Law [2e] Arcadia p10, Monstrous Supplement p18-19 (formian worker, warrior, myrmarch, queen); Tales from the Infinite Staircase [2e] p7,11,30-43,71; Planewalker’s Handbook [2e] p101

Source: Rip van Wormer, original page archived here

For Pathfinder 1e rules on playing a formian as a PC race, look here