Techno-Ecology of Mechanus

Greetings, esteemed traveller of the planes. Allow me to introduce myself—Professor Darles Mechanborough (planar human druid [he/him] / Fraternity of Order / LN), planar unnaturalist, humble scholar of multiversal ecosystems, and proud member of the Fraternity of Order, Extraplanar Zoological Department. You may call me Professor. My colleagues jest that I spend more time gallivanting through the planes than poring over dusty tomes in Sigil’s libraries, but I assure you, both pursuits are critical to my work. To study cosmic natural law, one must not merely theorise; one must observe—take a spin around the cogs of Mechanus, and immerse oneself in the tick-tock of existence itself.

My current endeavour, my dear cutter, is an ambitious Grand Catalog of the techno-ecology of Mechanus, that realm of precise flora and fauna which are peerless in their punctuality and ingenuity. Some think of Mechanus as a cold, lifeless machine—but those of us in the Fraternity of Order, those who yearn to understand the intricacies of law interacting with nature, we know better. Here, life itself marches in perfect time to the beat of order. Flowers bloom symmetrically and simultaneously, and migratory birds fly in delightful parabolic patterns. Mechanus teaches us that even in the most rigid of systems, life persists with ingenuity and beauty.

I have studied these rotating lands for decades now, carefully chronicling the flora, fauna, and yes, even the pests that call this great machine home, from the smallest clockwork beetle to invasive interplanar vines. A naturalist’s journey is never linear, nor is it predictable, but it is always rich with insights. Whether it’s cataloging the migratory patterns of the sprocket bats or deciphering the complex ciphersongs of the polished cogling birds, every moment on Mechanus deepens my understanding of a plane utterly resplendent in cosmic purpose.

Of course, my loyalties to the Fraternity demand more than mere observation. My reports are sent back to Sigil, to our headquarters in the City Courts, where they are carefully disseminated, preserved and studied. To understand Mechanus is to inch closer to understanding the great machinery of existence itself. A lofty goal, to be sure, but one well worth pursuing. And so, I continue my explorations amid the whirring, turning, singing harmony of the Clockwork Nirvana. A lifetime of study, adventure, and discovery: what more could any scholar wish for?

—Professor David Mechanborough

On the Structure of the Clockwork Jungle

Ah, Mechanus. She is a plane entirely unlike the lush jungles or teeming reefs we so often associate with life. Yet, even here—in the endless expanse of interlocked, ever-turning metal—life, in its relentless ingenuity, finds a way. And what a marvellously strange and enchanting ecosystem it is! So pull up a pew, and let me take you on a tour through this truly unique plane—a realm where machines and nature blur together.

To begin, dear cutters, we must first consider the landscape of Mechanus itself. This is a vast expanse of interlocking gears, some the size of a Prime city, turning in precise synchronicity. These gears form the fabric of Mechanus. There is no natural soil here, nor oceans, nor forests. Instead, the ground beneath your feet is an enormous, slowly rotating cog, and instead of clouds and sun the skies above are filled with an endless cascade of shifting machinery. It may sound cold—lifeless even—but nothing could be further from the truth. Mechanus, you see, is a plane of intricate precision, and life here has evolved—or, perhaps, been engineered—to fill every conceivable niche. You just need to know where to look for it.

On the Flora of Mechanus: Plants of Metal and Motion

The flora of Mechanus is most unexpected. Take, for example, the springflower, a plant-like organism that clings to the teeth of the great gears. At first glance, this vine resembles a delicate, metallic lattice, its leaves shimmering with copper and brass hues. Indeed, it can be hard to tell where the plant ends and the metalwork of Mechanus begins! The springflower vine feeds on the electric currents generated by the gears’ rotation. Its tendrils seek out exposed conduits, siphoning energy in a way as natural to it as the love of sunlight is to a rose bush on the Prime. But be careful! For the springflower is able to utilise the energy it has harnessed for defensive purposes as well. When threatened, the vine emits a spark of static electricity, discouraging hungry predators with a harmless—for humans—but startling jolt.

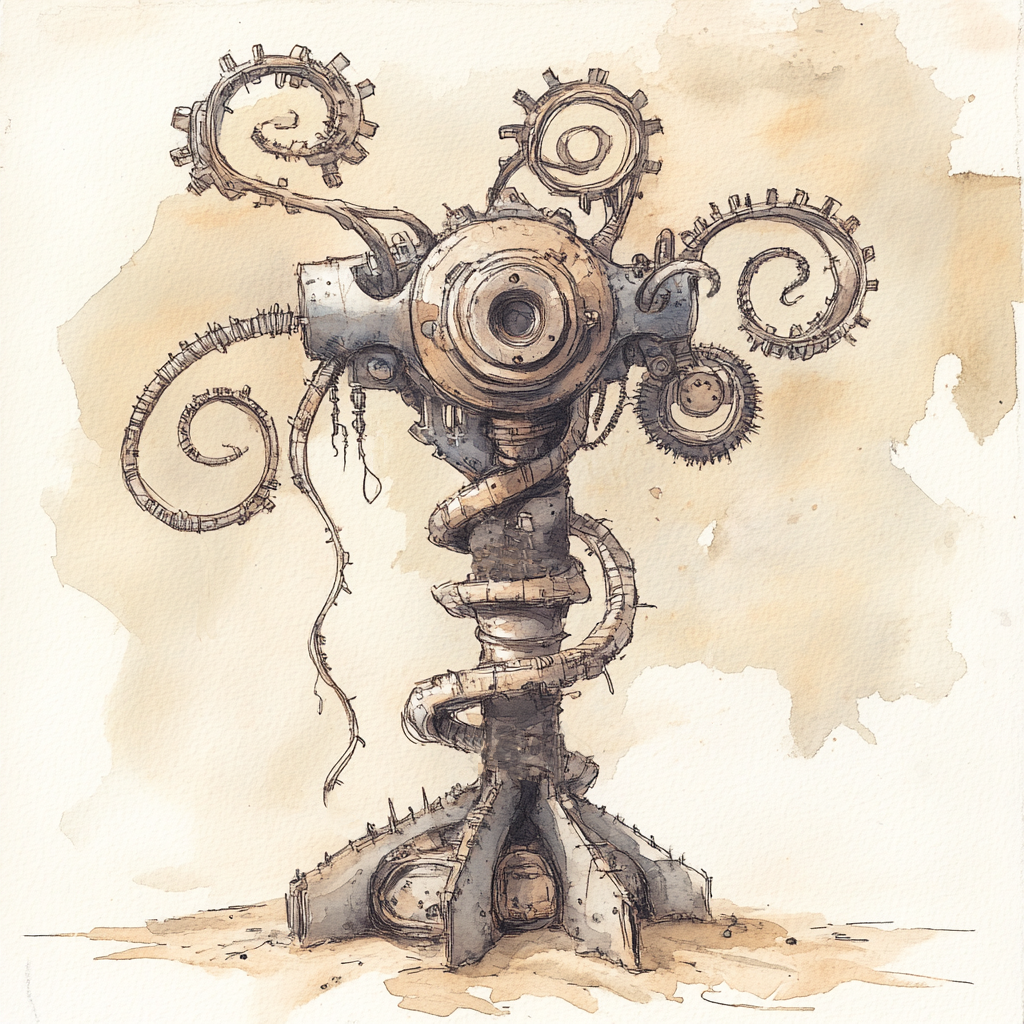

Another clockwork wonder is the gearfruit tree, truly a wonder to behold. These sturdy, mechanical eversbronze saplings grow in the crevices of large cogs, their branches forming intricate fractal shapes of polished steel. Gearfruit trees don’t produce blossoms—they produce nuts and bolts. Their gleaming chrome fruits, drop during Season Three—Mechanus’s equivalent of autumn, bouncing along the rapidly turning surfaces of the gears. Modron workers are tasked to gather these fruits, preferably before they fall, because they can clog up the great machine rapidly if allowed to accumulate. However, they are also useful, because they are the perfect size to use as replacements for worn-out parts. This is one of many examples of symbiosis I have observed in Mechanus; without the modrons the gear fruit would be problematic for the machinery of the plane, however with the modrons working in tandem with the tree, the net result is a great benefit.

I know one should not have favourite children, but I have a particular soft spot for logic moss, which forms a soft, shimmering carpet of glowing filaments that grows across the undersides of smaller gears. The patterns it creates are fascinating, networks of lines arranged in great circuits, where the light at junction points glows more brightly. Together they form constellations, each of them unique to the gear they are growing on. Once you learn the detail of the pattern, it is possible to identify the gear like a fingerprint—and I believe this may be how modrons navigate the plane so efficiently. This moss is neither plant nor fungus but something wholly unique to Mechanus. I believe it feeds on minuscule vibrations, growing only where the hum of motion is consistent. Its soothing glow produces Mechanus’s equivalent of twilight, guiding planewalkers through otherwise darkened parts of the Machine. I have observed that logic moss is a favorite perch for the elusive cogling birds—a critter we shall meet shortly.

On the Fauna of Mechanus: Living Mechanisms

Now, what of the fauna, you ask? Well, Mechanus teems with creatures engineered to mesh perfectly with the order of the plane. Consider the clockwork beetle, a miniature, whirring insect-like creature whose colourful carapace glints with golden filigree. These beetles scuttle along the gearshafts, industriously rolling away debris and ensuring the mechanisms remain in pristine condition. While mostly harmless, they can become quite grumpy if disturbed, releasing a burst of steam from the tiny vents on their backs as a warning hiss. They have an uncanny knack for tinkering, often repairing malfunctioning mechanisms with their tiny, precise legs. Some primes call them the janitors of the Mechanus. Quaint, isn’t it?

Then there are the coglings, who I find one of the most charming of Mechanus’s denizens. These little mechanical birds are fashioned from polished brass, their wings ticking like pocket watches as they flit from gear to gear. Coglings thrive by scavenging stray nuts and bolts, which they carry back to their nests—delightful constructions resembling spiraling, metallic towers. They’re a chatty bunch, too, chirping in high-pitched whistling tones that some planar scholars believe mimic the rhythms of Mechanus itself. Their chirps appear to be some sort of code, with short and long trills that occur in repeating patterns, although its complexity has so far eluded my ability to decipher. Coglings are also, unfortunately, notorious kleptomaniacs! Many a planewalker has complained of missing tools or trinkets, only to later discover them adorning a cogling’s nest high above. Aye, it’s harmless mischief, but amusing nonetheless.

Larger and more intimidating are the mechanoceros, lumbering beasts that seem to straddle an unusual line between predator and maintenance worker. These massive creatures—imagine a mechanical rhinoceros with exhaust pipes—wander the great gears, feeding on residual metal shavings and stray bits of scrap. Despite their fearsome appearance, mechanoceros are docile unless provoked. However, when threatened they are ruthlessly efficient, attacking in formation to trample foes, or stabbing with their horns and throwing opponents directly into churning gears—which never ends well for the victim. The lumbering hulks can also be helpful, and have been known to guide lost planewalkers by gently nudging them toward safer paths, or towards entry points of the Labyrinthine Portal. I have seen domesticated versions of these beasts too, used to pull specially-constructed carts.

On the Modrons as Farmers of Machines

One of the most fascinating aspects of Mechanus’s ecology is the symbiosis between its intelligent beings and the creatures of the plane. The modrons, for instance, are not merely enforcers of law. Some modron clades also take on roles as caretakers of the ecosystem. You’ll find them tending to fields of gearfruit trees or directing orderly lines of clockwork beetles to particularly dense patches of debris. It’s a magnificent cycle: the flora supports the fauna, the fauna maintains the gears, and the modrons shepherd the creatures to power the ecosystem. Pure harmony.

And let us not forget the role of the axiomatic oozes, quivering puddles of green-hued liquid quicksilver that consume impurities in the great gears and excrete pure, refined alloys. They are Mechanus’s version of fungal decomposers, playing a vital role in recycling and renewing the plane’s resources. Despite their unsettling, gelatinous appearance, they are harmless to most creatures, content to slurp away and reprocess waste material.

On the Migration of Mechanical Marvels

Some of the most astonishing phenomena of Mechanus are its migratory species, whose movements not only echo the grand clockwork rhythms of the plane but occasionally align with the rotation cycles of specific gears. Chief among these are the flame-powered sprocket bats, a species of mechanical flying creature that glints like burnished brass as it reflects the ambient light. They roost in the hollows of larger iron gears, where they use their magnetic claws to cling on upside down. These dazzling creatures migrate in astonishing, synchronised formations known as Chiroptic Legions, taking wing as one when a particular sequence of gears aligns just right. The route they follow is geometrical, weaving intricate, parabolic patterns through the air, as if sketching invisible blueprints across the plane.

Why do they migrate? Well, it appears to be tied to their diet. Sprocket bats feed on pinion flies, tiny motes of flickering energy that flit about the Great Machine. The bats’ migrations follow whatever pathways the pinion flies take, and the flies, curiously enough, always seem to drift toward areas of great portal activity—perhaps to absorb traces of interplanar energy. The bats’ journey is not without peril, of course; many a planewalker has had the misfortune of getting caught in a low-flying migratory swarm, only to emerge with singed hair and a newfound appreciation for sky goggles.

On the Mating Rites of the Polished Hourglobe Birds

Courtship on Mechanus is, predictably, a ceremony of structure and spectacle. Chief among these rituals are the elaborate mating displays of the polished hourglobe birds, a cousin species of the brass coglings. Hourglobe birds, however, are distinctly larger, with spherical bodies of glass and mechanisms so delicate they sound like windchimes in flight. During mating season—which coincides with the alignment of 12 major planar gears—the males gather in that towering spiral of machinery known as the Axle of Pi, which rises up from the centre of Radian, that burg of the Mathematician sect.

These axle acts as an amphitheater for one of the grandest performances Mechanus has to offer. The males soar into the air and begin to pirouette, catching and reflecting the light of Mechanus’s glow in dazzling kaleidoscopic patterns. The females, meanwhile, perch silently at the edges of the chiming cogs, watching intently. The competition is fierce, with males vying for attention by performing ever-more complex aerial acrobatics. Once a female hourglobe has chosen a mate, she joins him in a breathtaking synchronised flight that mimics the turning of interlocked gears.

On the Clockwork Vermin of the Machine

Even in Mechanus imperfections can occasionally arise. And when they do, they often take the form of its smallest, most vexing inhabitants: the clockwork vermin. These tiny mechanical pests, while fascinating in their design, pose problems to the smooth operation of the plane’s endless gears. Let us examine, dear cutters, how even a plane of perfect order wrestles with the chaos of the smallest disruptions—and how these issues are kept in check.

Clockwork vermin are minuscule mechanical creatures, often forged unintentionally by the plane itself. While Mechanus is a realm of supreme precision, it is also a realm of infinite scale, where even the most carefully designed systems occasionally produce oddities. These vermin vary widely in form and function but share certain characteristics: they are small (often no larger than a human hand), metallic, and instinctively drawn to the workings of Mechanus’s gears.

Unlike the larger, more harmonious creatures I have described already, these vermin often disrupt the balance of Mechanus, causing stutters in the plane’s machinery or introducing inefficiencies into its otherwise perfect operations. Though their behaviour is not malicious—they follow instinctive patterns—they are considered nuisances by the modrons, who view them as anomalies in an otherwise flawlessly functioning design.

Springspinners are arachnid-shaped vermin with needle-thin legs and small, beady lenses for eyes. They get their name from the metallic webs they weave across Mechanus’ gears. These webs, composed of thin strands of conductive metal, were once believed to be helpful in redirecting energy flows. However, they have recently been discovered to increase the chance of sparking or shorting out crucial systems. Springspinners are prolific breeders, laying tiny, gear-shaped eggs in the crannies of machinery. If allowed to infest an area, they can coat entire sections of the plane in their glittering but obstructive webs.

Perhaps the most infamous of Mechanus’s pests, the geargrubs are small, segmented creatures that resemble worms made of brass and copper. They wriggle through the plane’s intricate machinery, gnawing on soft conductive metals like insulation wires or sprockets coated in protective alloys. While their feeding habits rarely do catastrophic damage, geargrubs are known to cause localised disruptions, slowing or stalling the turning of smaller gears. Left unchecked, a large infestation can cascade into larger inefficiencies across the plane.

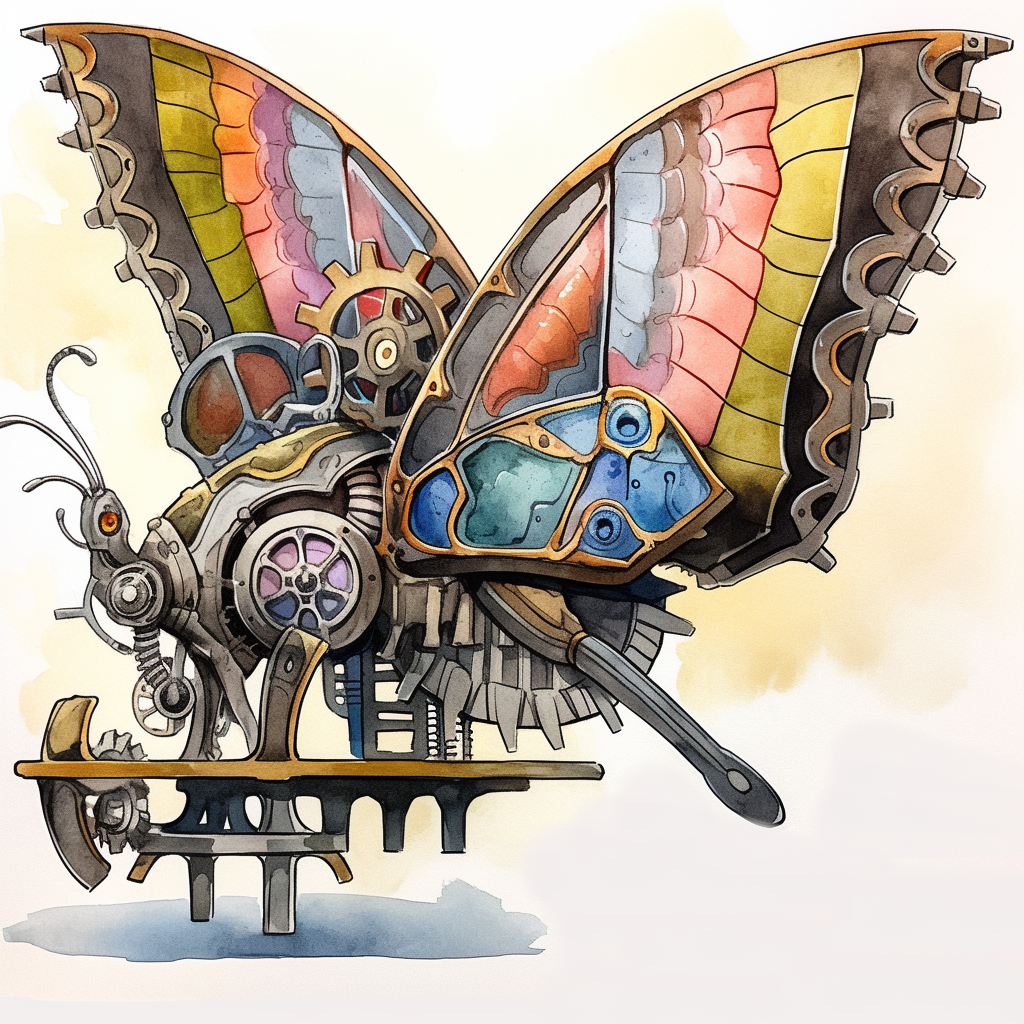

One of Mechanus’s more destructive vermin, rustmoths are small, butterfly-like creatures with colourful wings of oxidized metals. While they are pretty, they cause problems by consuming the protective lubricant coating that modrons routinely apply to Mechanus’ machinery, leaving raw metal vulnerable to rust and friction. While Mechanus itself is resistant to most forms of corrosion, rustmoth activity causes subtle vulnerabilities in its sub-systems, requiring modrons to constantly patrol for damage. The moths are also maddeningly evasive: their erratic flight patterns make them hard for modrons to catch, and their tendency to roost near moving gears makes removal dangerous for would-be exterminators.

Conclusion

And so, dear cutter, Mechanus reveals itself to be not merely a sterile plane of cold order but a lively, thriving ecosystem where life and law intertwine—if one looks closely enough. Its countless technological niches have given rise to wonders of metal and motion, a strange symphonic beauty that humbles even this jaded scholar. I hope that this little jaunt has sparked in you a sense of wonder for the clockwork world, where every wild timepiece—be it a beetle, a vine, or a mighty construct—has a place in the design of Mechanus. After all, if even this place can teem with life, perhaps there’s hope for any corner of the multiverse.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ve just spotted a particularly unusual cogling nest, and I’d be remiss not to sketch it for my journal. Until next time, mind the gears—and keep your screws about you!

See Also: Mechanus

Source: Jon Winter-Holt. Thanks to PlasticMowhawk for the original inspiration.